Working together by listening to each other

At a workshop at B. Braun's innovation lab, an interdisciplinary group of experts searches for answers to the big questions of the health care system.

It's an experiment. It's also the start of a dialog process with which B. Braun is opening up more in order to share expertise.

The heavy, red metal door on the ground floor of the former factory building is a border: Daily routine and business as usual need to be checked here. Whoever crosses this threshold and ascends the steps needs to be ready to engage with new ideas and perspectives. A quote by racing driver Mario Andretti hangs on the wall: "When everything seems to be under control, you are not going fast enough.” A poster in the staircase demands: "Leave your comfort zone." By no means is everyone ready to do that.

Welcome to werk_39, B. Braun's innovation lab

"This is a neutral location," says Anton Feld, design thinking expert and moderator, as he makes the final preparations in the spacious, open workshop area. At werk_39, B. Braun engineers and technicians work on new products and together with hospital teams work on improving efficiency in the OR. The belief is that, even in the 21st century, there is no tool more powerful than the human brain. All it takes is the right conditions for it to work properly.

„We support workshop participants with mentoring and analysis, and help identify problems and pain points.“

STEP 1: INITIATE

On this late-winter day in Tuttlingen, Germany, product design has taken a back seat to a bigger problem: "How can you increase efficiency and fairness in the health care system?" Experts from all over Europe have traveled to this multidisciplinary workshop. Health economist Axel Mühlbacher is here from Brussels. WHO adviser Ilona Kickbusch is here from Bern. Doctor and startup entrepreneur Paul Brandenburg is here from Berlin. Together with philosopher Weyma Lübbe, IoT expert Tobias Gebhardt and surgeon Florian Sommer, they have come to talk about the future. But not with the usual talk show logic, where buzzwords swirl around and everyone defends their own position. Instead, they are leaving their comfort zone and coming together for a common purpose.

„It's an experiment. We don't know what we're going to get out of today. That's exactly what's so exciting! “

STEP 2: DISCOVER

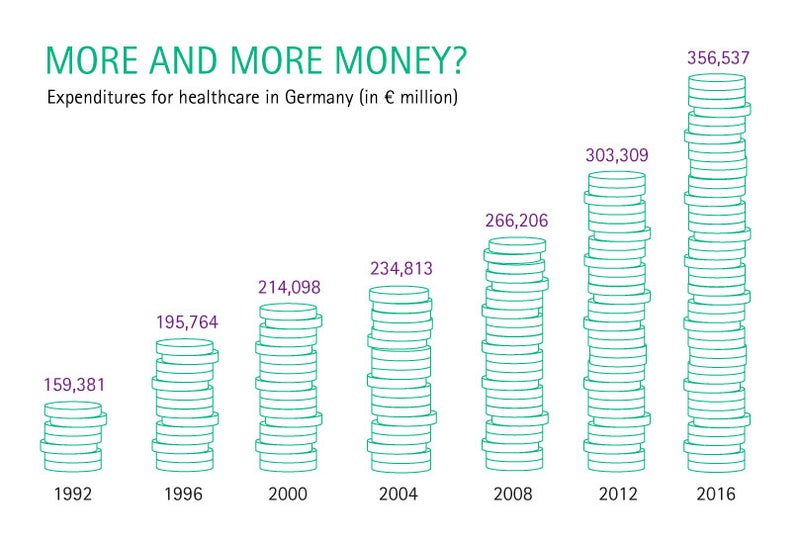

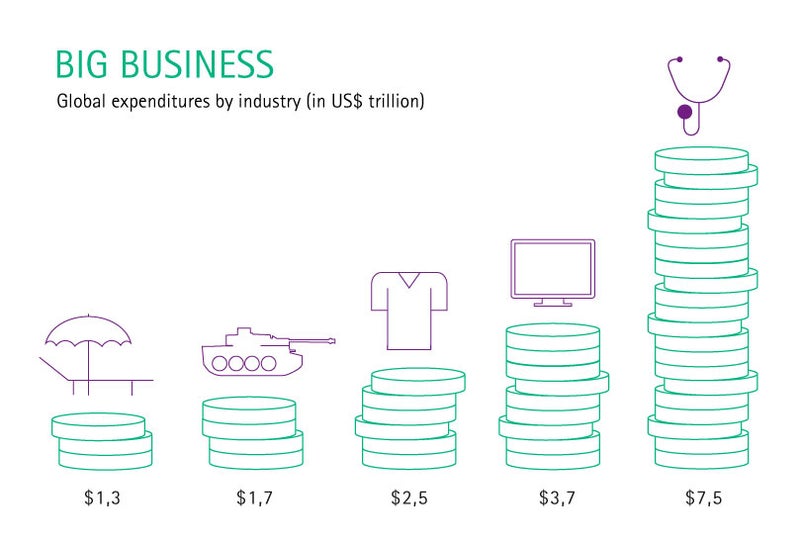

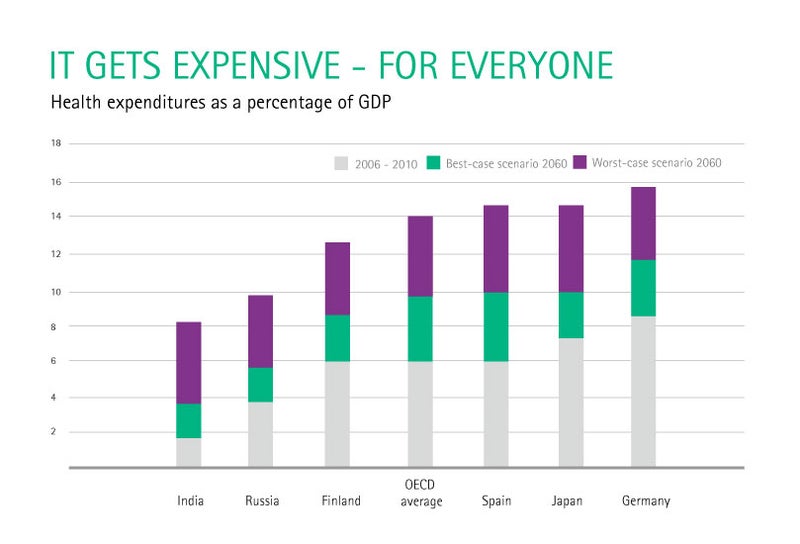

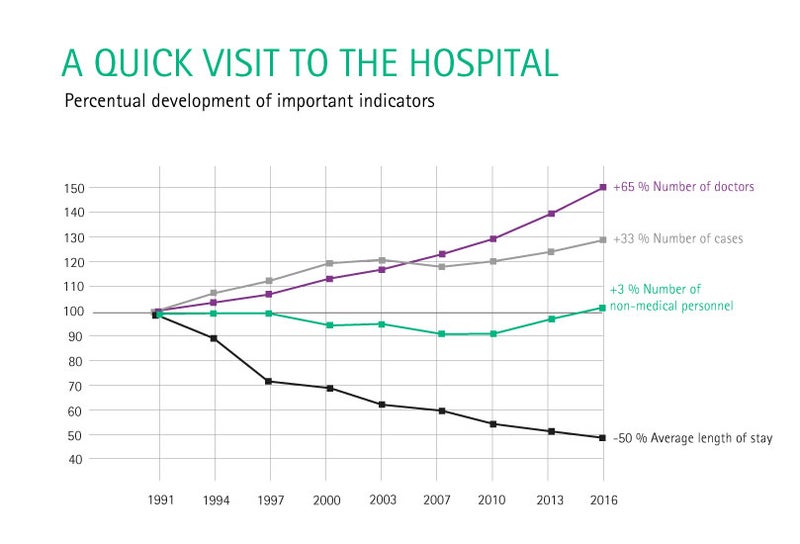

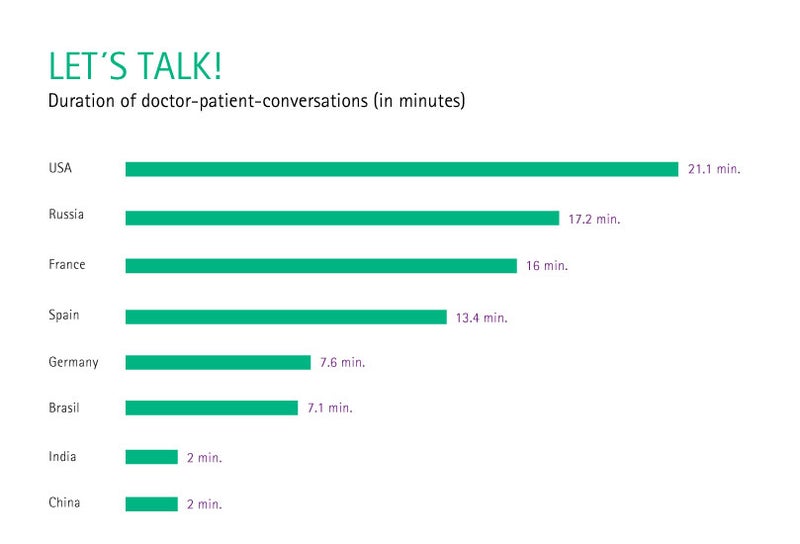

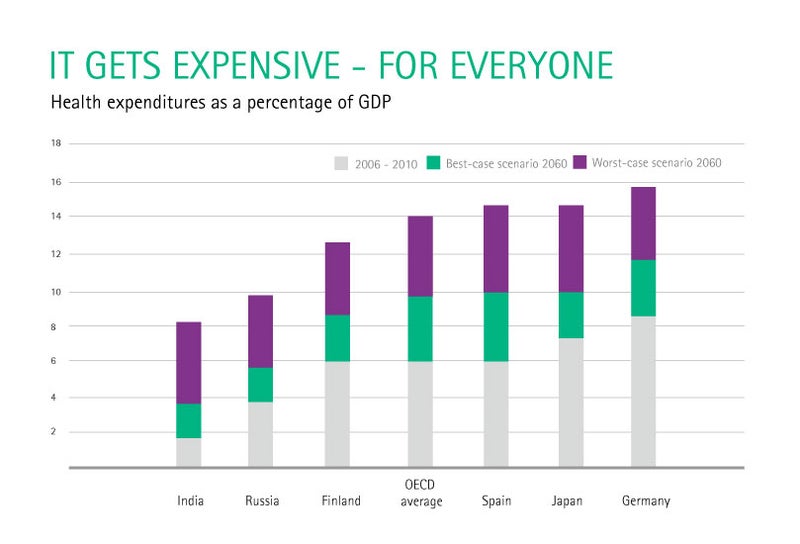

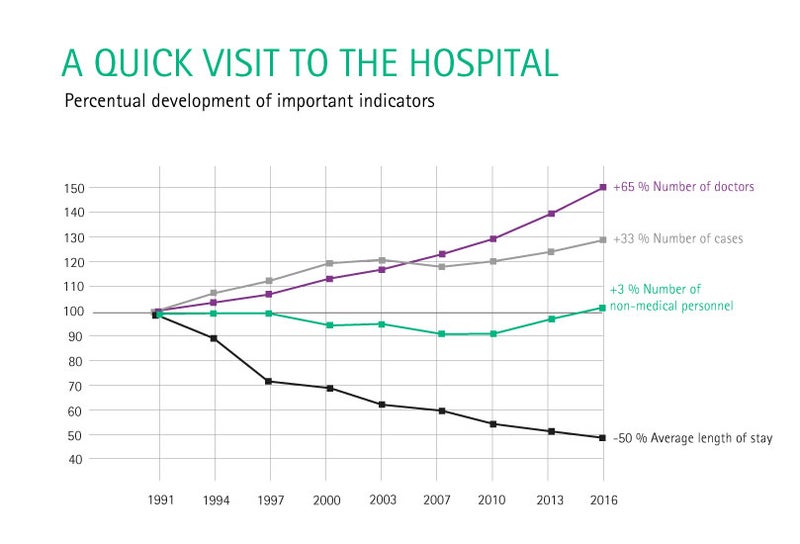

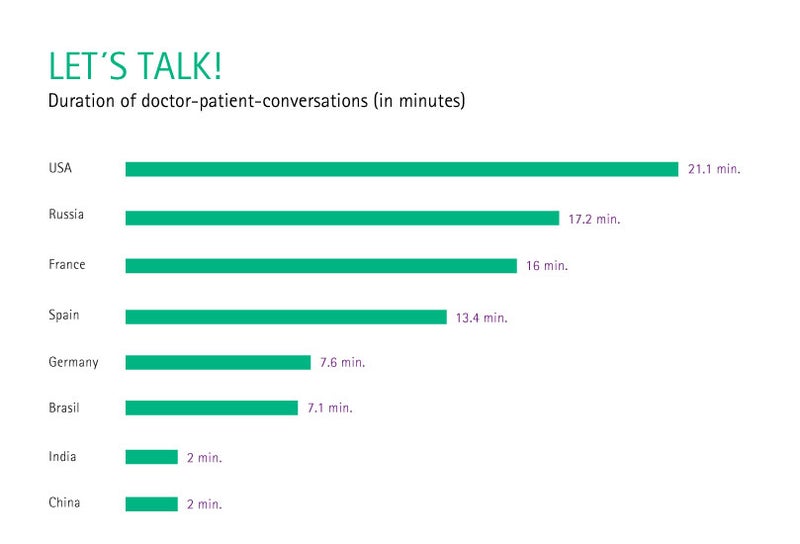

A maximally fair and efficient health care system: Let's take a quick step back. Germany spent 374 billion euros in 2017 on it. That's almost 11 percent of Germany's gross domestic product - in 1992, it was just nine percent. And, according to the OECD, global health care costs will more than double by 2060. At the same time, the poor in Germany have a life expectancy that is up to ten years shorter than the wealthy. What can be done?

The group pauses, gets acquainted, and then begins to discuss the topic. The workshop is less podium led and more of an open group discussion. It takes some getting used to. First, they take some notes. Terms. Approaches. Definitions. With a green magic marker, Feld writes everything down on a large whiteboard. It's a "brainstorming-friendly atmosphere", as he puts it.

Axel Mühlbacher: “If I'm being honest, I don't know exactly what fairness is. And so far, there hasn’t been any accepted approach to make efficiency in health care measurable. So, something huge would have to happen if we come up with a eureka moment in six hours." (laughs)

Weyma Lübbe: “We would also actually have to talk about the historical intellectual relationship between fairness and efficiency. How did it come that economists focused on efficiency and let other disciplines think about fairness?"

Paul Brandenburg: ”Are those even the right terms?”

Ilona Kickbusch: ”Here, it goes without saying that people have a right to health. But that's not the case for 50 percent of humanity. They become sick and poor at the same time.”

Markus Strotmann: “It's up to us to find the point of leverage of our discussion. What does a health care system need to do?”

STEP 3: EXPERIMENT & BUILD

10:30 a.m. Coffee break. Yet, instead of receeding from the debate or withdrawing into the privacy of a smartphone screen, the workshop participants just keep going: forming small groups, talking, doubting, thinking - doing work. Werk_39 establishes a connection between the analog origin of B. Braun and the digital and knowledge society. On the side, historical C-clamps from the factory serve as holders for informational materials.

Workshop supplies, like pens or post-it notes, are kept in old wooden toolboxes. The modern information architecture of smartphones, projectors and WiFi stands in contrast to unplastered walls, exposed timber framing and cable looms - the inner workings of the building are out in the open.

„We tend to forget the principles behind the methods. We only look at the artifacts.“

And that's exactly what it's about: looking underneath the surface. The workshop participants agree to limit the discussion to two questions and divide into two groups:

Group A: Access to the health care system

Phrases swirl around the huge room: "Picking up the pace", "That's really paradoxical", "Only 15 percent of patients know exactly how the system works", "If it costs nothing, it's worth nothing". Stop listening to the work group of Strotmann, Kickbusch, Sommer and Gebhardt for just a minute and you will lose track. Manager, doctor, political scientist and startup founder complement each other well and find common ground: "Everyone has the right to access the health care system."

Tobias Gebhardt: "Improving access means better control."

Florian Sommer: "What do you mean by that, exactly?"

Tobias Gebhardt: "Yes, we should specify that."

This statement forms the foundation of a matrix they are designing on the whiteboard with post-it notes and lines of red and green magic marker. One thing quickly becomes clear: No one can solve this problem alone. There are no dials you can turn and everything will get better or even become good. The people need to take more personal responsibility. The insurance companies and employers need to use incentives to reward efficient behavior. The service providers need to develop a variety of treatments and offers that really help people. It all has to come together. Good thing people are working together.

Group B: Fairness vs. efficiency

The second workshop group chooses another, more structured approach for their discussion. Philosopher Weyma Lübbe, economist Axel Mühlbacher and doctor Paul Brandenburg sit around a small, round table and carry on a quiet, yet heated debate. There are also repeated flashes of intellectual enjoyment between the counterparts when their discussion partners come up with new, clever formulations or exaggerations. Nevertheless, they agree on the goal: "A major part of the problem is not undersupply, but oversupply that is not for the sake of the patients."

Weyma Luebbe: “Absolutely right. But this is not an innovative proposition yet.”

Paul Brandenburg: “For a lot of people out there, it’s not trivial: They think the system works. And a lot of money is lost in the process. How do we put an end to that?”

Axel Mühlbacher: “Without measuring patient benefit, there can be no measurement of efficient health care.”

Weyma Lübbe: “What does efficiency mean to you? A shift in the distribution of goods in which at least one person is better off and no one is worse off? Or do you mean shifting funds to the most productive place?”

Axel Mühlbacher: “What about: Patient benefit is oriented on fairness.”

Weyma Lübbe: “The benefit of what patient? That’s the issue when we decide about who gets what. And then, fairness is the clincher, no value among others. No-one drives health care policy with sentences like ‘Though this action is unfair, it is on balance a useful thing’. And this is a good thing.”

Axel Mühlbacher: “So, efficiency comes second to fairness. Even I would subscribe to that from a social perspective.”

Paul Brandenburg: “At the same time, a wasteful system is necessarily unfair.”

"The patient needs to be able to precisely rate the net benefit of a treatment - like weighing the side effects of cancer treatment against the additional time that might be won."

"The patient needs to be able to precisely rate the net benefit of a treatment - like weighing the side effects of cancer treatment against the additional time that might be won."

STEP 4: TRANSFER

Normally, by the end of a workshop day, the debate has become more and more structured. The participants prioritize the most important topics through methods—methods like dot voting, where you put little colored dots on preferred approaches. Focus is on next steps, to-dos and road maps. And, naturally, the B. Braun workshop has also developed many ideas for how the health care system can better master the challenges of the 21st century:

- The wrong incentives promote the misallocation of funds.

- Quick, smart new ideas can save lives.

- Improving patients’ health skills - and the training of doctors and nursing professions.

At werk_39, however, it’s not about artifacts, it’s about the underlying principles. Maybe it’s time to get down to fundamentals. Especially when development is so fast, it’s difficult to distinguish opportunities from risks. This is why the B. Braun workshop is reshifting focus. “Of course, the health care system can’t be separated from the society,” says Ilona Kickbusch. “Especially since we live in a consumer society, everyone wants the next pill, the next treatment.” Conversely, this naturally means that the health care system can only be decisively improved through the employment of time, care, know-how and technology once society’s attitudes change. And that’s not impossible: “In palliative medicine, a lot has happened in the last five years,” says Florian Sommer. This elicits strong agreement from those present. “The new process takes fewer resources and provides patients with a better experience.”

And have we made progress on the issue of a fair health care system? “The theory about fairness is a difficult and controversial field, but nevertheless indispensable,” says Weyma Lübbe. “Many things can be somehow recorded when being clarified, such as fairness doesn’t mean establishing equality. That is to say that all of us are most equal when we are no longer alive.” The room goes silent for a moment. Everyone is reflecting. In a podium discussion or talk show, everyone fights for talking time. Here, everyone listens to each other. “Sometimes you do have to be a philosopher,” says Markus Strotmann with a musing smile.

„I’ve learned a lot. The conversation will continue.“

One workshop is never the end point. It’s just the beginning of a process. Were all problems solved? Of course not. Was it worth it? Absolutely!

What's left from the workshop day

The expert’s workshop at werk_39 was just the beginning of a lasting, exciting process. We would like to discuss the following questions with you:

- What positive incentives get people to be healthier and put less strain on the health care system?

- How do we improve the health skills of patients, nurses, doctors and management in the digital age?

- How do we determine the patient benefit of treatments in the most rational way possible—and avoid futile care?

- What new technologies are promising?

- What values do we as a society need to discuss to lasting improvement in the health care system?

Do you want to participate in our discussion? Send us an e-mail at lets-talk@bbraun.com.

We look forward to your input.