A lot more than just saving blood

Blood is scarce and expensive. Additionally, current studies have shown that a blood transfusion is a risk factor for higher hospital mortality and numerous health complications.

For these reasons, and based on existing guidelines and evidence, patient blood management has been introduced at the University of Frankfurt Medical Center. Three key measures aim at optimizing the use of donor blood transfusions:

1. Special pre-treatment of high-risk patients before surgical procedures

2. Minimization of blood loss during and after the operation

3. Standardized test to determine whether a blood transfusion is actually reasonable

The usual practice of red blood cell (RBC) concentrate transfusion varies a lot throughout the world. With more than 50 transfused RBC concentrates per 1,000 inhabitants, Germany occupies the first place in Europe and worldwide as well (for comparison purposes, Australia has 36, the Netherlands 34; Norway 42; Great Britain 36; Switzerland 41).1,2 However, due to medical and societal changes, banked blood will become an increasingly scarce resource. A highly promising approach to a solution is the multidisciplinary patient blood management (PBM) concept, whose implementation is incidentally promoted3 by the World Health Organization (WHO) and presented below.

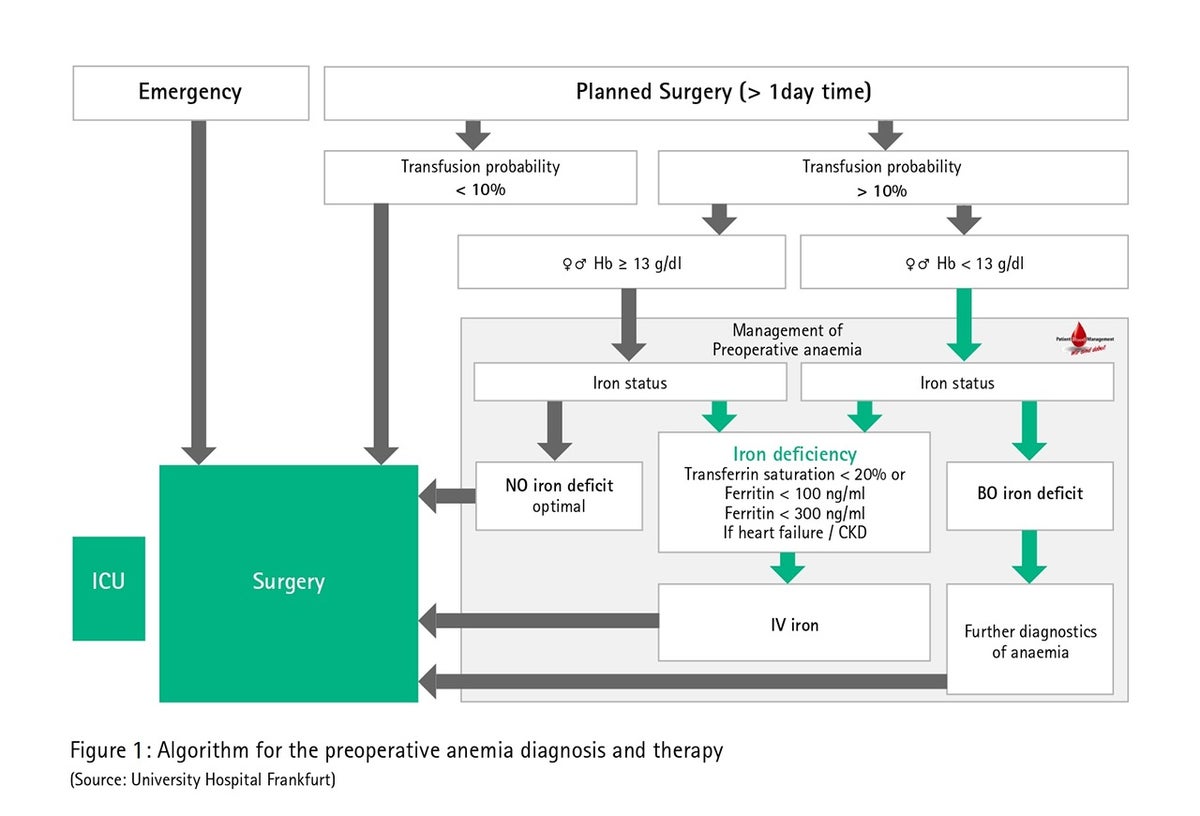

Diagnosis and therapy of preoperative anemia

According to WHO criteria, there is anemia when the hemoglobin value falls under 12 g/dl in women and under 13 g/dl in men. Musallam et al. report a 30% prevalence of preoperative anemia in an entire age group of 227,425 hospitalized patients.4 In the hospital, preoperative anemia is one of the strongest predictors for the administration of RBC concentrate during or after surgery. In addition, preoperative anemia must also be classified as stand-alone and independent risk factor for the occurrence of postoperative complications and higher postoperative mortality.4 In principle, every anemia should be clarified whenever possible before surgery and non-urgent procedures postponed until the respective anemia treatment has ended.6 A British study revealed that preoperative anemia correction in close collaboration with family physicians was able to reduce the incidence of preoperative anemia from 26% to 10% on the day of the operation and the risk for an intraoperative donor blood transfusion by more than half, from 26% to 13%.6

In German everyday situations, the cost of intravenous iron therapy, the separation of outpatient and inpatient care as well as the potential postponement of the procedure are the arguments often given against preoperative anemia treatment in a discussion. Compared to donor blood transfusions and apart from the cost and budgetary aspects, preoperative anemia treatment could also be worthwhile for the patients themselves (fewer transfusion-associated risks and side effects, better healing processes), for the hospital (patient recruiting and marketing) and for the general public as well (scarcity of banked blood, faster rehabilitation). Fig. 1 shows an algorithm for the preoperative anemia diagnosis and therapy using the University of Frankfurt Medical Center as an example.

Minimization of unnecessary blood losses and protection of the body’s own reserves

Perioperative blood collection and procedural interventions could result in iatrogenic anemia.7 Thus, a weekly blood loss of up to 600 mL can occur in intensive care patients due to bloodwork alone.8 A current high estimate indicates an annual blood loss of 25 million liters of blood for the western world alone, taking current laboratory blood collection standards into account, and this inevitably leads to hospital-acquired anemia.9 Reducing the size of the small blood collection tubes and a daily strict indication can significantly reduce collection quantities and unnecessary blood losses without adversely affecting diagnostic quality.10

Mechanized autotransfusion (MAT)

Technical aids like mechanized autotransfusion play an important role both during and after the operation. Starting with an estimated intraoperative blood loss of 0.5 – 1 liter, the preparation of the blood lost during surgery is regarded as reasonable as it has proven to lower the use of donor blood banks.11 Likewise, the use of MAT in tumor patients after previous irradiation of the blood lost12 during surgery or by using special leukocyte-depleting filters13 should be considered.

Perioperative management of anticoagulants

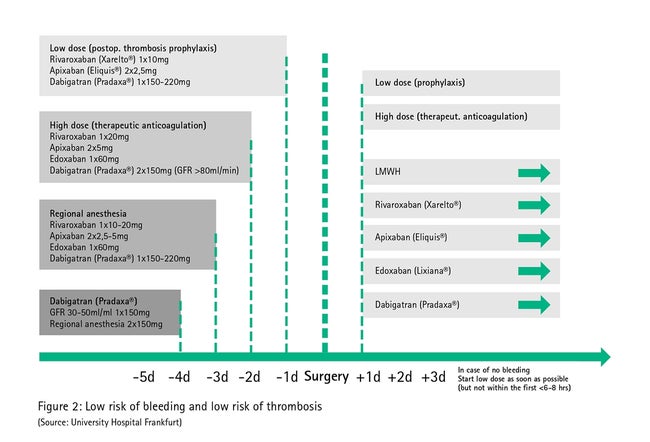

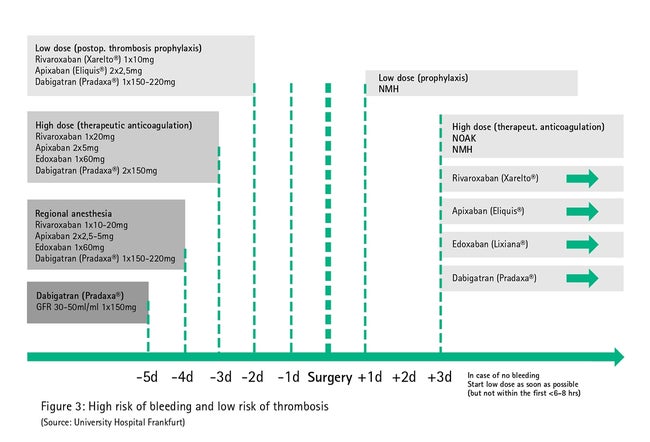

About 1 – 3% of the population receives anticoagulants permanently to prevent arterial and venous thromboembolisms or after a stent procedure. Depending on the indication, heparins, (direct) oral anticoagulants or thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors can be used here. A non-critical taking of the medications until the day of surgery would be accompanied by a very high hemorrhage risk. However, a general early discontinuation of the medication would be just as irresponsible because otherwise thromboembolisms or stent sealings would occur. Against this background, local standards for dealing perioperatively with anticoagulants should be laid down, e.g. as part of a patient blood management project.

Early individual risk stratification, e.g. in the anesthesia outpatient clinic, should consider the following factors: indication for anticoagulation – risk profile for thrombosis and hemorrhage, co-morbidity (kidneys, liver, bone marrow), co-medication (platelet aggregation inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-rheumatic drugs), urgency of the operation, regional anesthesia, hemorrhage risk owing to the planned operation (low/moderate/high) and the change of anticoagulation (bridging/switching).14

Fig. 2 describes direct oral anticoagulant management in low-bleeding procedures (those in which surgical hemorrhages are rare or those in which surgical hemorrhages are easily controllable due to their localization, e.g. dental treatment, dermatology). Here, owing to the short half-life, no mechanized autotransfusion in the perioperative phase is generally needed as the necessary break in therapy can be achieved by simply omitting it before surgery.

Since various co-morbidities (e.g. impaired kidney and liver function) and co-medications (e.g. co-anticoagulants) can be associated with relevant hemorrhagic tendency in spite of a 2-fold half-life break in therapy, anticoagulation therapy with direct oral anticoagulants must be paused early (5-fold half-life, Fig. 3) in procedures with high bleeding risk in which a clinically significant hemorrhage cannot be ruled out (large abdominal operation, large vessel operation, large orthopedic operation, large intrathoracic surgical procedure, puncture of non-compressible vessels).

Intraoperative coagulation management

Appropriate and careful surgical bleeding control is the basis for prophylaxis and the efficient therapy of perioperative hemorrhages. Besides, basic physiological conditions like pH > 7.1, ionized calcium > 1.2 mmol/L and temperature > 36 °C are the basic prerequisites for optimal blood coagulation (hemostasis).15 If there is the slightest suspicion of hyperfibrinolysis, anti-hyperfibrinolytic drug therapy with tranexamic acid, for example, should be started.16 However, cell-mediated (primary) hemostasis can be improved with vasopressin analogs (desmopressin), for example.17 Any other follow-up therapy must build on this basic therapy, whereby the algorithm-based therapy of bleeding patients, in particular, allows effective and economical management. The primary objective of coagulopathy must be the causal therapy of the problem and not the symptomatic therapy with donor blood substitution.

Transfusion practice variability and transfusion-associated immunomodulation

Transfusion practice, especially with regard to the administration of RBC concentrate, varies a great deal in different countries and hospitals, which allows one to conclude that there is uncertainty concerning the appropriate indication and that possibly unneeded allogeneic blood products are being transfused. 2,18 This large variability in the usual transfusion practice is all the more surprising because clear recommendations for dealing with blood products were expressed in Germany by the Cross-Sectional Guidelines of the German Medical Association.12 They recommend taking the criteria of the patient’s hemoglobin concentration, compensation ability and risk factor criteria into account.

Regarding the potential risks of RBC concentrate, the transfusion-associated transfers of bacteria, viruses, parasites or prions as well as not immune-mediated adverse drug effects (e.g. transfusion-associated volume overload, hypothermia, hyperkaliemia, citrate overload, transfusion hemosiderosis) are known.19

In addition, the transfusion of cellular blood preparations, as “transplantation of the liquid organ blood” represent in fact an immunological challenge for the recipient organism too instead of blood group compatibility. The immune-mediated risks include:

- Allergic transfusion reaction

- Febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reaction

- Transfusion-associated acute pulmonary insufficiency

- Hemolytic transfusion reaction

- Transfusion-associated graft vs. host disease

- Transfusion-associated immunomodulation

The long-term importance that is in store for the transfusion-associated immunomodulation is the subject of clinical research. Ultimately, RBC concentrate – like other medications with a relevant spectrum of adverse reactions – should be administered in an exclusively rational and medically indicated way. For example, by using a computerized requirement system for allogeneic RBC concentrate with a programmed decision algorithm based on guidelines and documenting the respective transfusion trigger in Stanford (USA), the share of RBC concentrate administrations that do not adhere to the guidelines were lowered from 66% to under 30% between 2009 and 2012 of all transfusions and the total quantity of RBC concentrate by 24%.20

Conclusion

The main focus of a multimodal PBM is to protect and strengthen the patient’s own resources. This can be achieved by recognizing and treating anemia, meticulously minimizing perioperative blood loss, restricting diagnostic blood collections, having evidence-based coagulation and hemotherapy concepts as well as a guideline-compliant, rational indication of RBC concentrate. The effects of a PBM concept on German hospitals is being scientifically investigated in multiple centers.21

Patient Blood Management helps to save blood

Patient blood management (PBM) was introduced at the University of Frankfurt Medical Center in July 2013 in order to protect and exploit the patient’s own blood resources. Moreover, during and after the operation, more blood-saving work is being performed than ever before: During the organization, it is ensured that the patient’s blood coagulation is working well and the blood lost in surgery is prepared for its return. For its dedication, the hospital received the 2016 Patient Safety Prize, awarded annually by the Patient Safety Active Group. The Aesculap Academy in Tuttlingen is one of the prize sponsors. Patient blood management allows doctors to reduce the need for blood transfusions by ten percent, thereby lowering the risk of acute kidney damage for the operated person and also the costs involved. A study conducted with 130,000 patients has proven the benefits for patients. Already more than 100 hospitals across Germany are working on the introduction of the PBM concept.

By Prof. Dr. med. Patrick Meybohm and Prof. Dr. Dr. med. Kai Zacharowski

Contact

References

1. Hofmann A, Ozawa S, Farrugia A, Farmer SL, Shander A: Economic considerations on transfusion medicine and patient blood management. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013; 27: 59-68.

2. Van Der Poel CL, Janssen MP, Behr-Gross ME: The collection, testing and use of blood and blood components in Europe: 2008 Report. https://www.edqm.eu/en/blood-transfusion-reports-70.html (last accessed on 20/12/2014.

3. World Health Organization (WHO): The World Health Assembly. Resolution on availability, safety and quality of blood safety and quality of blood products (WHA 63.12) http://www.who.int/bloodsafety/transfusion_services/self_sufficiency/en/ (last accessed on 20/12/2014.

4. Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, et al.: Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011; 378: 1396-407.

5. Goodnough LT, Maniatis A, Earnshaw P, et al.: Detection, evaluation, and management of preoperative anaemia in the elective orthopaedic surgical patient: NATA guidelines. Br J Anaesth 2011; 106: 13-22.

6. Kotze A, Carter LA, Scally AJ: Effect of a patient blood management programme on preoperative anaemia, transfusion rate, and outcome after primary hip or knee arthroplasty: a quality improvement cycle. Br J Anaesth 2012; 108: 943-52.

7. Qaseem A, Alguire P, Dallas P, et al.: Appropriate use of screening and diagnostic tests to foster high-value, cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156: 147-9.

8. Koch CG, Reineks EZ, Tang AS, et al.: Contemporary bloodletting in cardiac surgical care. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99: 779-84.

9. Levi M: Twenty-five million liters of blood into the sewer. J Thromb Haemost 2014; 12: 1592.

10. Ranasinghe T, Freeman WD: 'ICU vampirism' - time for judicious blood draws in critically ill patients. Br J Haematol 2014; 164: 302-3.

11. Wang G, Bainbridge D, Martin J, Cheng D: The efficacy of an intraoperative cell saver during cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesth Analg 2009; 109: 320-30.

12. Vorstand der Bundesärztekammer auf Empfehlung des Wissenschaftlichen Beirats: Querschnitts-Leitlinien (BÄK) zur Therapie mit Blutkomponenten und Plasmaderivaten. 2014; 4. überarbeitete Auflage.

13. Catling S, Williams S, Freites O, Rees M, Davies C, Hopkins L: Use of a leucocyte filter to remove tumour cells from intra-operative cell salvage blood. Anaesthesia 2008; 63: 1332-8.

14. Giebl A, Gurtler K: [New oral anticoagulants in perioperative medicine]. Anaesthesist 2014; 63: 347-62; quiz 63-4.

15. Kozek-Langenecker SA, Afshari A, Albaladejo P, et al.: Management of severe perioperative bleeding: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013; 30: 270-382.

16. Crash- trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, et al.: Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 23-32.

17. Weber CF, Dietrich W, Spannagl M, Hofstetter C, Jambor C: A point-of-care assessment of the effects of desmopressin on impaired platelet function using multiple electrode whole-blood aggregometry in patients after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 702-7.

18. Gombotz H, Rehak PH, Shander A, Hofmann A: Blood use in elective surgery: the Austrian benchmark study. Transfusion 2007; 47: 1468-80.

19. Goodnough LT, Murphy MF: Do liberal blood transfusions cause more harm than good? BMJ 2014; 349: g6897.

20. Goodnough LT, Shieh L, Hadhazy E, Cheng N, Khari P, Maggio P: Improved blood utilization using real-time clinical decision support. Transfusion 2014; 54: 1358-65.

21. Meybohm P, Fischer D, Geisen C, et al.: Safety and effectiveness of a Patient Blood Management (PBM) Program in Surgical Patients - The study design for a multi-centre prospective epidemiological non-inferiority trial. BMC Health Services Research 2014; 14: 576.