Only life and death together are the entire existence

Rahel Mann does not fear death – yet she should have plenty of reasons to fear it because she survived World War II as a Jew in Berlin. Nowadays, restless Ms. Mann works in a Berlin hospice as a volunteer.

She is now 79 years old and can look back on an eventful life, having always served others. She worked as teacher, writer, psychotherapist, doctor, non-medical practitioner and spiritual adviser.

Ms. Mann, you work as a dying person companion?

I have been working at the hospice for three years and also care for homebound patients. The hospice, which is attached to the Wenkebach hospital, has 15 beds on two levels. Each patient has their own room, pretty but also fully isolated. There are wards where patients can be rolled in their beds to common rooms. I think this is better because when you can’t get out of bed any longer, then you become lonely, also or especially as a dying person.

Can you describe your job?

I am the main relationship for the persons being cared for and if I’m lucky, I am also present when they go. The last man I cared for had been born in 1937, like me. He had lived as a German in the U.S., where he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. When his cancer started spreading, he returned to Berlin for treatment and to spend his final days here. After three days in the hospice, his pain intensified so much that he received morphine every four hours. When I visited him, he told me that he had already said good-bye to his daughter so she wouldn’t have to experience his passing. He also said good-bye to me because he knew that he wouldn’t last a week with the morphine. Wonderful, I told him, then you won’t have to suffer so long. He died shortly thereafter at night.

What did he appreciate so much in your attitude?

He told me that he was so thankful to have received the last greeting from me. He did not want to overtax himself and others with his deterioration. That impressed me and I experienced it only that one time. It is a blessing for us that we are allowed to leave due to old age or an illness. Many doctors and caregivers think that they must lengthen life as long as possible, but this means languishing for months or even years and is really terrible.

I am not a person who would like to keep hoping for any price because it often doesn’t serve us. There is a saying, “You shouldn’t stop the dying” or “Travelers should be allowed to go, regardless where.”

Have you made provisions for yourself?

I have recorded everything in writing so my children don’t become compassionate and leave me lying somewhere for years. If I am still conscious, I will immediately stop eating and then fall asleep peacefully with morphine. In the event that I am unconscious, I definitely won’t last long because I have refused artificial respiration. Additionally, I have joined the German Association for Dying with Dignity. In the event that it is permitted to provide help when dying, they can give me something.

My second life partner took his own life because he was very sick. He jumped from the 6th floor. I understood him and would have no problem with it either if there were no other way out. I think that when push comes to shove, I will do what is necessary.

What does working in the hospice has to do with your life story? Aren’t you afraid?

I grew up with death as a child, it was natural for me. Every life ends with death. There is an old wise Jewish saying that there is a whole life only when life and death come together.

The older I get, the happier and easier I can deal with it. I become repeatedly aware of how many things I accomplished that were important to me in spite of the war. That’s almost a miracle.

Nonetheless – isn’t it eventually enough one day?

Maybe it sounds strange, but I think that it is very important to help others while saying to them that one’s whole life should be seen as beautiful and death as something harmonious. Most people don’t want to think about that. I feel that it is a wonderful task to help someone view death from another perspective.

Ultimately, death is part of a whole. It has nothing ugly or repulsive for me. We tend to consider only the beautiful to be perfect – but this is wrong. Only the good and the bad together are perfect.

What does a dying person need?

A dying person needs absolute loving attention. Without words. That’s the most important thing. And I always say “with joyful dedication” because people immediately feel it.

Do you give them strength?

Yes. As soon as you accept both, namely strength and weakness, life and death, you become strong. Not just me, but also the others. I give them that and I don’t even do it consciously, I just allow that.

Does believing in a religion play a role?

Generally speaking, not in the last minutes. I only experienced it once when a man said just before he died: “So now it’s good and God can do what He wants.”

I once accompanied a mother of two daughters who had left the church. She didn’t believe in anything and everybody reproached her for that. I strengthened her in her decision to do what was best for her.

The way I see it, faith is a compensatory act that inhibits the basic trust in the spiritual principle. The old Hebrews explained it like this: There is a primal force inside us when we die. Then we only live from the spiritual power of the universe, which connects all of us with one another. I find that a lot more important than belonging to a church. Incidentally, there is no word for faith in Hebrew. Emona, the word that is nowadays translated as faith, really means trust in the sense of basic trust.

When accompanying the dying person, what is one of the deadly sins for you?

A deadly sin for me would be to force people to eat.

Have you sometimes have had a conflict between “being a doctor” and accompanying?

No. When someone wants to be helped to prolong his life a little more and live better, he is given that. When someone has reached the point to leave, he gets the help to fall asleep peacefully. To show up and say “You really can’t” or “You may not” is wrong for me.

When you visit the dying person, you are a stranger – is this an advantage or disadvantage?

It is an advantage. Most dying persons wear a mask in front of their friends and relatives. They don’t want to show their true feelings and pass away “nicely.” For this reason, many die shortly after visitors leave the room. I feel it’s good that that the patients don’t know me as well. As a person, I either have immediate access or I don’t take the case. For some people, I’m too direct.

You appear to be so self-confident, do you sometimes feel that you can do something wrong?

I get my confidence because I believe that even if I behave in the wrong way, it benefits the other persons, who also need my mistakes to decide on their own. To think that one can always do it correctly and well is hubris.

Do you have a wish when the time comes?

I had a heart attack in 1980 and wish to just drop dead. I think that the right person will be on my side at the right time. I don’t need anything else.

„Death is only a transformation. It is my task to communicate this to the dying person.“

An interview conducted by Andrea Thöne

Rahel Mann: Vitality lies in the here and now

Those who meet Rahel Mann cannot evade her. She is outspoken, asks personal questions without hesitation and takes a stand. She wants to understand those opposite her, no detail escapes her. Even at the age of 79 she is full of energy; her voice reveals no sign of age and tiredness. Everything has a purpose, she says and gives the dying something of her strength in this way when she visits them.

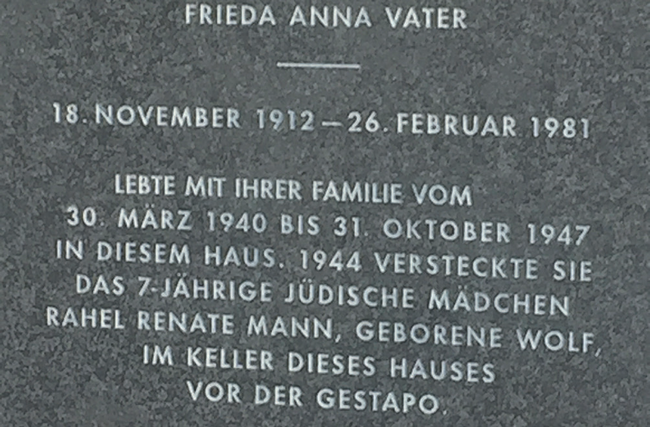

Her attitude is anything but a matter of course because death confronted Mann very early. Born in Berlin as a Jew in 1937, she is the result of a night without obligations. She never knew her father, who was assassinated by the Nazis. She never fit into her mother’s world, as she says. When her mother was deported in 1941, strangers hid her, thereby saving her life. She survived the last six months of the war in a cellar shack in a house in Berlin-Schöneberg.

This is where Mann learned how to read herself and also to live self-sufficiently, to make something out of the present. This continued like that after the war too. When her mother had to spend a long time in the hospital with an active tuberculosis, she was on her own again. “Doesn’t matter,” she says while moving her hand dismissively. She liked to be without supervision.

However, then comes the other side, a suicide attempt at 17, because not everything is possible after all. She wrangles with the guilt of having survived, keeps a diary and writes poems. That gave her the strength to carry on: high school graduation, psychology degree, marriage, medical school, two children, a son and a daughter, two stillbirths, divorce. She worked in a naturopathic practice as early as when she was studying medicine. The second intensive partnership came to an end too. Another relationship was out of the question for her afterwards. “Men want to decide even if they are so nice,” she says while resolutely folding her arms. In this way, she took the path to become independent in 1980. Mann moved to Brunswick, where she opened an office for psychosomatics, homeopathy and neural therapy, not as physician, but deliberately as non-medical practitioner – to obtain her freedom, as she says. She treated many cancer patients who had turned away from conventional medicine.

“Not hoping and waiting, but doing” (Ovid), is her slogan. Therefore, she closed her practice upon turning sixty, emigrated to Israel to be with her daughter, studied the Kabbalah there and learned Hebrew. At some point, her fear of bombs stopped her from sleeping. “The diarrhea returned,” she says. “Do you really want to live through this again, mom?” asked her daughter. Thus, Mann returns to Berlin in 2007, moved from her house on the sea in Ashdod to a one-bedroom apartment on the fifth floor in western Berlin, where she is very close to heaven.

Mann is not apprehensive about confronting death and – in addition to her commitment as a contemporary witness in schools and universities, she began an apprenticeship as a death companion. It helps to deal with one’s own death, she says. She carried on even when diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014. She regards her work as hospice companion as a human service because she gives others the strength so they can reclaim something positive from the situation after all. “It was an important insight for me when I was in the cellar as a child that moaning would only make my own life harder”, she says. Afterwards, she never feared death any longer, it had always been her friend. “Death is only a transformation. It is my task to communicate this to the dying person.”